News & Events - Archived News |

| [ Up ] |

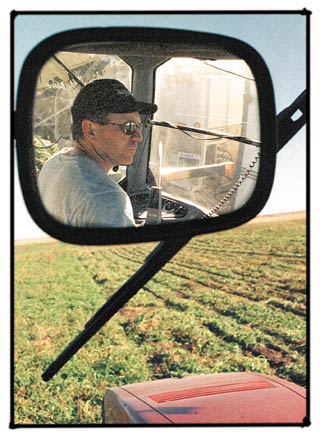

Farming for the produce aisle in Eastern Montana |

| By

Jim Gransberry, The

Billings Gazette October 7, 2001 |

NORTH OF BROCKTON On

benchland north of the Missouri River in Montanas northeastern corner,

Craig Steinbeisser is a bit frustrated with the pace of the potato

harvest.

Potatoes on the prairie is just one of several experiments nowadays conducted by both professional researchers and farmers who want alternate crops for dryland and irrigated ground. The emphasis is on produce that puts more cash in the farmers pocket. Among the other nontraditional crops getting a tryout along the Yellowstone and the Missouri rivers before they converge just across the border in North Dakota are carrots, onions, cabbages, pumpkins and dry beans of every shape and color.

In addition, the harvest was going slow because the ground was a bit too moist, the vines tangled the equipment and a second digger was down for repairs. Despite his slight frustration, Steinbeisser was jovial. What the heck, it could be worse, he reckoned. There were much worse locations this September compared to his little-recognized corner of Montana. Eventually, the Sidney-area familys experiment would benefit both them and the neighbors, he said. We should get maybe 350-400 bags per acre, Steinbeisser estimated. Potatoes are measured by 100-pound bags or hundredweights. The soil is well-suited for potatoes, which like a sandy medium in which they can expand. The patch here is the first for this location. Near Williston, N.D., the Steinbeissers have 400 acres of russets being harvested for shipment to J.R. Simplots processing plant in Grand Forks or for storage in a new warehouse north of Williston. The new facility holds 150,000 hundredweights of spuds. The storage facility was built before last seasons harvest, said Don Steinbeisser Jr., who was harvesting sugar beets near Sidney. It is for long-term storage, he said. The last shipment of potatoes from 2000 were loaded out the 7th of July. Some of the familys production was tested at the AVIKO processing facility in Jamestown, N.D., which processes 800,000 pounds of potatoes each day and produces 250 million pounds of frozen french fries and specialty potato products a year. The J.R. Simplot Co. plant at Grand Forks is one of eight owned by the Idaho corporation and produces 400 million pounds of frozen potatoes a year. One of the ironies of the market nowadays is that in 2000-01, the table potato industry collapsed as a result of a production glut, and million of tons of spuds were given or thrown away because they could not be sold. At the same time, the United States became a net importer of french fries because Canada had built potato processing plants near producers and because the cheaper Canadian dollar made it profitable to buy french fries north of the border. One reason for the experiments in the Sidney-Williston area is the hope of attracting a food processing plant. The potatoes being harvested at Brockton were headed directly to Grand Forks, N.D., 412 miles from the field. The key to better income from alternative crops, whether irrigated or dryland, is a contract, said Don Steinbeisser, Jr. What is needed is a long-term contract, said his cousin Russell, who supervised the cleaning of the potatoes taken from the Brockton field. The processors wanted long-term storage, Russell said. The cousins have a five-year contract for the potatoes and get a payment for the storage, too. The Steinbeissers are a twofold, family farm corporation. Don Sr. and his brother Joe are one separate unit. Joes sons, Russell and Joey, farm with their cousins Don Jr., Craig and Jim. The division of labor allows for at least one owner-manager to supervise the harvest of sugar beets, corn, barley and hay. It can be something of a nightmare, Don Jr. said, Howd we do it before cell phones? On a small scale, onions are also being grown by a couple of farmers. The essential cooking bulbs are one of Jerry Bergmans crops this year. Experimental plots at the Eastern Agricultural Research Center at Sidney boast onions, cabbages, two types of potatoes reds and russets and dried beans. Bergman is a plant breeder who is superintendent of agricultural research centers in both Sidney and Williston, N.D. Last year, Bergman said he tried carrots but did not have an industry cooperator this year to test carrot varieties. He has also tried broccoli. Industry cooperators, such as seed companies, have become essential partners in agricultural research, he said, because state funding has been flat for the past 20 years. In addition to finding new varieties that suit the Mon Dak area, he is also looking at the right sequence of crops to provide a four-year rotation regimen for irrigated crops using sugar beets; malt barley or corn; potatoes or other root vegetables; and malt barley, beans or corn. The Mon Dak region refers to the northeastern portion of Montana and northwestern North Dakota. Although divided by a political border, the region is the premier U.S. growing area for durum wheat, which is used to make pasta. The climate and the soils are similar on both sides of the line. Bergman and others see the region as a future garden. Two-thirds of the U.S. population lives east of the Mississippi River, he said. We have the product advantage over the West Coast. Mike Carlson, coordinator for the Eastern Plains Resource and Conservation Development, said, If we had a city with a million people within a 100 miles, wed have more vegetable gardens than you could imagine in your life. The Eastern Plains RC&D encompasses 16 Montana counties in the eastern third of the state. Bergman sees the region supplying produce to cities such as Denver; Regina, Saskatchewan; and Winnipeg, Manitoba His goal is to draw a food processing center to the area. Ive been criticized for promoting the area rather than Sidney or Williston, Bergman said. I will support anyone who develops a processing plant. The one who makes the best offer, gets it. The location does not matter because the region is the winner. This is a great place to live and we want to create jobs here.

Gazette reporter Jim Gransbery recently spent a week in the northeastern portion of Montana. This report is the first of an occasional series examining business in the region |