News & Events - Sugarbeet Update Magazine |

Fall 1999 |

One Hundred Years of Sugar Beets and Michigan Sugar Companyby Rod Stewart Daenzer, freelance writer and Sarah Zagata, communications intern, Michigan Sugar Company

Nineteen hundred and ninety-nine marks the centennial anniversary of Michigan Sugar Company’s Caro sugar processing facility. It also marks a century of successful sugar beet farming in Mid-Michigan. When you purchase a bag of Pioneerâ Sugar, you become a part of the sugar industry’s rich history in the Great Lakes State. Eating Pillsbury, Dannon, General Mills and Hunt Wesson products is a celebration of 100 years of Michigan’s only American-owned sugar company—and America’s oldest operating sugar beet processing factory. In the age of globalization, it’s comforting to enjoy the sweet taste of American-made goods. A rich tradition and history looms behind the 25-ton trucks laden with beets, passing by on brisk, fall days. The story begins in 1884, when Saginaw printer Joseph Seaman was traveling in Germany and realized how the sugar beet crop thrived in the temperate climate. A second trip convinced Seaman to send seed samples to Dr. Robert Kedzie, a chemistry professor at Michigan State Agriculture College. Kedzie’s enthusiasm for the crop motivated him to import 1500 pounds of beet seeds from France and distribute them to farmers across the state. This dedication gave birth to a new, vital agricultural industry in the state and earned Kedzie the title "Father of the Michigan Sugar Industry."

The inaugural processing facility opened its doors on October 17, 1898, in Essexville, Michigan. (The factory no longer exists today.) During the 126 days of the initial campaign, 32,000 tons of sugar beets were processed. The excitement of the new crop that had spurred confidence in its growers was spreading throughout the state. One year after the Essexville processing facility opened, Caro town banker Charles Montague accumulated enough money from investors in Detroit to construct the Caro facility. The Sugar Tramp illustrates the excitement and nostalgia of the undertakings, "What happened behind the scenes in Detroit is now legend, with color added. Equipped with a generous role of greenbacks, Montague convened in his hotel with a group of moneyed men. The sight of the modest farmer and his "roll" suggested a friendly round of poker. All night they played. At dawn the game was over. Montague had all the money together with enough signed pledges to assure the construction of the works." Returning to his hometown a hero, Montague had stirred commotion unlike any seen before in the small community. One hundred acres were donated for the factory site and the Caro Water Company pledged 500,000 gallons of water per day. Comprised of seven board members, the Peninsular Sugar Refining Company was formed to oversee the monumental events that would soon unfold and change the Caro community forever.

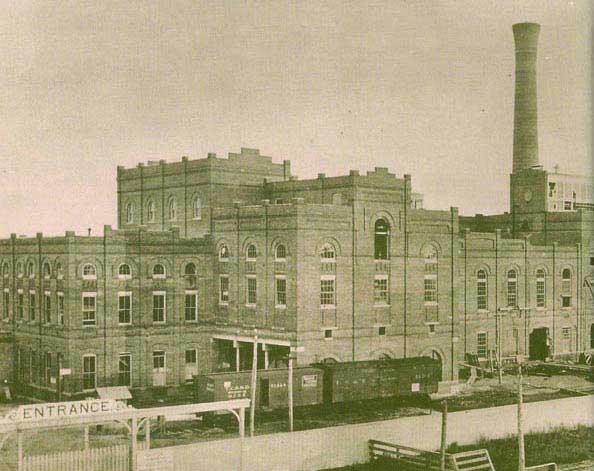

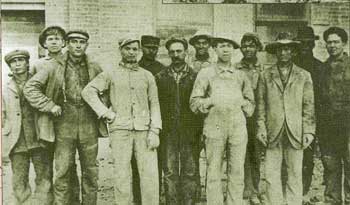

The newly formed company hired A. Wernicke Construction to begin the building process. The reputable German company had recently completed an Australian factory and had the experience of 200 other factories under its belt. The construction company signed a $300,000 bond guaranteeing the new factory would be completed and producing sugar at three cents a pound by September 1, 1899, a mistake that would be detrimental for A. Wernicke Construction. With excitement of a new industry lingering in the air, Caro became a bustling madhouse. Farmers labored away on their sugar beet crop while the Germans and Caro citizens toiled at the new factory. Six million bricks, 1000 cords of stone and twenty-seven carloads of machinery later, the factory was finished just in time for the county fair on October 5th. However burdensome the work, the laborers managed to enjoy the fiasco. Survivors of the Caro crew recalled memories of the most joyous construction camp of their lives. Part of that joy spurred from the renowned Longshoremen Cocktail, consisting of three fingers of whiskey, a beer and a cigarette. For the workers, baseball games and beer barrels were as standard as bricks and cement. With music from the village band and an unlimited supply of beer, perhaps the most colorful festival thrown was the farewell Bacchantian Boozery Banquet. With many difficulties surrounding the initial campaign, the three-cent contractual agreement was unable to be met, and the Peninsular Refining Company took A. Wernicke Construction to court. A court order reduced the factory price from $400,000 to $125,000, a sweet settlement for the small town and sour deal for the Germans. Caro citizens were able to remodel the factory before the next campaign, and the area where broken parts and debris were thrown was referred to as ‘Wernicke’s Graveyard.’

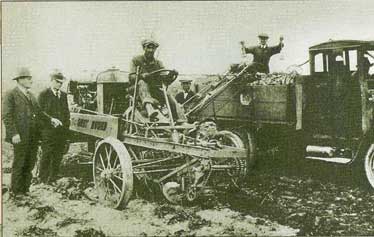

The fond memories of the early campaigns are still vivid within the minds of those who worked them. Over a steaming cup of coffee at the local McDonalds, Gordon Sayers, 79, remembers his experience in sugar history from 1937 to 1940. "I loved my job. Thirty-three cents an hour was the first real money I ever made." His friend Leo Cambell, 78, recalls filling and stacking bags for the campaigns of 1941 and 1942. "We hired in for 37 cents plus a bonus if you worked the whole campaign. It was hard, but if you stacked all the bags in an hour and a half instead of three, they paid you for three. With a twelve-hour workday, the money really added up." Across the street from the factory office, Don and Dick Witokvosky set up their antique tractors for a show at the Caro fairgrounds. The brothers worked during sugar campaigns; Don was a pipefitter and Dick traveled across the US and Canada retrieving machinery from bankrupt processors. Reminiscing about old times, Dick pointed to the far end of the fairgrounds, "Years ago, there used to be three boarding houses over there for campaign workers so they wouldn’t have to journey home every night. Near downtown there was a ten cent barn where workers could stable their horses ten cents a day and ride home at night." In addition to factory workers, sugar beet farmers have undergone numerous changes in their methods and capabilities. Paul Findley, who farms 2000 acres with his two sons, has witnessed the dramatic changes of the sugar industry. "My father and most farmers owned about five acres of beets back in the thirties. They used to let us out of school to harvest. That meant pulling the beets off by hand," explained Findley. With records that date back the early 20th century, Findley realizes the advances in production that have come with time and technology, "In 1906, farmers harvested seven to eight tons per acre. Today, that average is around 20 tons. Sugar beets are the most important crop in this area. Back in the forties farmers were self sufficient, but things change. You have to keep up to survive." Leaps in progress have come with the monogerm seed, laborsaving equipment, enhanced fertilizers, insecticides and herbicides, hybrids and improved management practices. One thing that remains unchanged is the importance and excitement of harvest, "I did take off for my wedding and honeymoon," stated Findley, "but not much else stands in the way during harvest season." Another unchanged factor is the strong relationships between Michigan Sugar Company and its growers. "We have always worked hand-in-hand with farmers, using the best seed and nutrients and the right pest and disease control." states Teresa Crook, chief agronomist for Michigan Sugar Company. "We’ve done research on many farms in Michigan to ensure our farmers have the latest information for growing a quality crop." The Michigan Historical Commission Memorial Marker stands proudly outside of the Caro Michigan Sugar Company office where Crook works. She remembers the factory’s rich history every morning she sits at her oak desk which came from the original Caro office that was torn down in 1974. Farmers, townspeople, and factory workers coming together for a common cause and community is an integral part of the sugar industry’s history. Like the 44-foot molasses pan donated to the town for a swimming pool, changes within the 100-year-old plant always involve the community in some way. Michigan Sugar Company and its growers continue to support the communities they serve. Donating over 60,000 pounds of sugar to non-profit organizations each year, in addition to supporting education, athletics, family, health and the arts, Michigan Sugar Company and its growers remain dedicated to the community for the next century and beyond. The centennial anniversary of the Caro sugar factory is about more than the factory building and the historical marker placed before it. The anniversary celebrates 100 years of people working to preserve the factory’s history, continue its production, and build upon its future for their families and community. |