|

By Lois Kerr

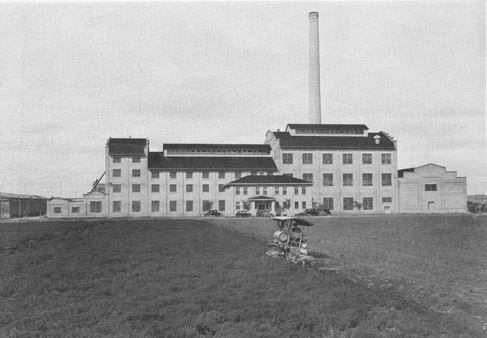

When construction began on the sugar factory in Sidney 75 years ago, the face of agriculture in the area changed practically overnight. In the years since the factory completed its first campaign, Holly Sugar has become a firm rock in the community, providing jobs, a strong source of tax revenue, and greatly enhancing the economic health of both the agricultural sector and of the entire area. Prior to 1925, area producers grew sugar beets to a small extent. R.S. Nutt grew the first sugar beets in 1911 for sheep feed, but with the coming of the railroad, more producers grew the crop to ship to Great Western Sugar in Billings. However, with the high freight rates associated with shipping beets to Billings, producers did not plant an overabundance of the crop. Area producers formed a Beet Growers Association in 1924 with the intent of attracting a sugar processor to the area. Shipping beets to Billings proved impractical, and producers wanted to see a sugar processor move to the Sidney area. They realized that in order to attract a processor, area producers themselves had to grow enough beets to support a factory. New producers began to experiment with beets along the Lower Yellowstone. Their efforts paid off with the procurement of a sugar processor willing to come to the area. Investors decided to build a sugar processing plant in Sidney, and to have the factory ready for the 1925 beet harvest. For that reason, the GN and NP railroads constructed rail spurs to the site of the soon-to-be-factory in December of 1924. In January of 1925, investors bought 10,000 shares of stock for building a sugar factory in Sidney. Investors knew that beets could be raised efficiently in the area, thanks to good soil and an abundance of water. As well, Sidney itself had excellent shipping facilities, with railroads leaving the town in several different directions. Holly Sugar had arrived in Sidney. It cost investors $1.5 million to build the original plant. One hundred teams hauled the necessary gravel for the concrete work from a mile and a quarter away. Jennison Brick Company of Fairview supplied 2,000,000 #1 hard burned common builders' bricks for the project. Holly officials bought most of the refining and processing equipment needed for factory operations from a plant in Anaheim, CA. During the construction, laborers commonly worked for

about 25 to 30 cents per hour. Producers in 1925 averaged 9.3 tons of sugar beets per acre, with the sugar content averaging 14.7%. Jacob Rau delivered the first load of beets to the new factory, and J.C. Johnson of Blue Rock Bottling Company bought the first 100-pound bag of sugar ever produced by the Sidney factory. In 1926 and 1927, contracted acres decreased slightly. However, in 1928, acreage increased and continued to increase up until the present day, with contracted acres now standing near the 48,000-acre mark. In the 1930's, the area sugar beet industry provided work for many people, who otherwise would have had nothing. Some people immigrated to the area in search of work, found work, and made this area their home. By 1933, sugar beet acres had increased to a little over 15,000. Producers increased their average tonnage to 12.75 per acre, and sugar content averaged at 17.18%. Holly built bulk sugar bins in 1937. Conditions remained fairly constant at the factory until the late '40s. In 1948, Holly Sugar replaced the Roberts Cell Type Battery, used for the removal of sugar from the freshly sliced beets during the initial stages of the sugar extraction process. The company replaced this battery, installed in 1925 as part of the original equipment, with a silver chain diffuser. Holly Sugar originally sold wet beet pulp to area growers. In 1959, factory officials installed a pulp dryer. This enabled them to make dry pellets from the wet beet pulp. Dry pellets created a better market, as they stored and shipped well. Holly and the growers enjoyed both good growing years and suffered through very poor years. The growing year 1959 proved to be one of the worst years ever. That year, 40% of the beet crop froze in the ground. Holly began expansion at the Sidney plant in earnest during the 1960's. Factory officials installed new equipment for use in the final stages of the sugar extraction process. This equipment included three continuous raw sugar pans, two white sugar pans and two white centrifugal machines. Factory officials then followed up the next year with the installation of two more automatic white centrifugal machines, crystallizers and evaporators. With expansion in mind, Holly continued to increase plant capabilities. Factory officials installed a 100,000-pound package boiler, improved the yard lighting and employee parking, and installed a sewage system. By the mid '60s the plant could slice 2,500 tons of beets on a daily basis. Up until 1963, the Sidney Holly plant owned and operated a steam locomotive, purchased in 1934, for use in switching operations. In 1963, Holly retired the steam-powered engine, replacing it with a diesel-powered locomotive instead. In 1966, Holly donated the old steam rail engine to the town of Sidney. Community organizations combined their efforts and successfully moved the steam locomotive from the Holly Sugar yard to the Sidney city park, where it remains on display today. In the earlier days of the factory, plant managers bought sugar beets by the ton. Growers did not bother with tare, nor did they generally know their individual sugar content. However, by the mid '60s, both sugar and tare became more important, with factory officials paying growers not only a straight price for tonnage, but also rewarding them for increased sugar content. For this reason, Holly built a tare and sugar testing lab in 1967. It then became possible for the factory to determine individual grower's tare and sugar percentages. In 1968, Holly continued to upgrade the plant and increase the slice capability even further, to 4,400 tons daily. Throughout 1968 and 1969, Holly implemented improvements and upgrades by replacing the silver chain diffuser, adding additional centrifuge machines, more filtration pumps, another pulp dryer, a bulk storage bin, a new thickener and upgraded the electrical system. Improvements and upgrades continued throughout the factory all through the '70s and into the '80s. In 1984, the factory spent $4 million to convert the plant back to a 60% coal fired operation. Natural gas costs had escalated enormously, particularly since the factory did not at that time have energy efficient systems. Factory officials greatly reduced fuel costs by converting two of the four gas boilers to a coal fired operation. Workers also installed heat exchangers and devised ways to use steam heat for several different operations. In short, Sidney Holly Sugar became as energy efficient as possible. The use of women in the factory greatly increased during the eighties. Women had always worked as clerks in the offices and in the labs, but in the '80s, women began working on the main factory floor. The oil boom in progress at that time created worker shortages, and women expanded into every available job in the factory. The concept of early harvest also began in the '80s. In order for the factory to handle more beets, yet still complete the slice by mid March, both harvest and slice had to begin earlier. Holly officials began the practice of early harvest in September, then commencing with regular harvest on Oct. 1. By the early '90s, Holly Sugar had improved equipment and technology to the point that the factory routinely sliced 5,500 tons of beets on a daily basis. In 1992, Holly officials removed the smokestack, a long time landmark of the Holly Sugar plant. The smokestack, no longer in use, began to deteriorate and officials, concerned about safety, removed this long-time landmark. In 1995, the growers and Holly Sugar constructed ten

new storage silos at the plant. Holly Sugar continued to improve and upgrade equipment in 1997 and 1998 with the improvement and expansion of the beet pile grounds, more beet receiving equipment, installation of additional pulp presses and improvements in the factory's ability to extract sugar. Holly also completed the huge new tower diffuser, added a new Cossette mixer, increased its thick juice storage capacity and added a fourth slicer. As Holly moved into its 75th year, the factory had the capability to slice 6,500 tons of beets daily. By the 75th campaign, Holly also had joined the computer age. Prior to the advent of computers, workers used gauges and meters to assist them in the extraction processes throughout the plant. Now, however, computers take the guesswork out of the sugar extraction process by monitoring the entire operation, checking every step along the way. Today, Holly contracts close to 48,000 acres of sugar beets. The company hires 450 employees to help with the harvest, and employs 250 people to work over the winter in the factory, processing sugar beets. Holly Sugar employs 87 people on a year-round, full time basis. Producers grew 1,102,956 tons of beets for the 75th sugar campaign, which corresponded to the 1999 growing season. Early harvest began on Sept. 5, and the factory finished the factory slice by March 7. They then spent an additional three weeks processing sugar from the thick juice stored in the thick juice tanks. The factory sliced an average of 6,100 tons of beets on a daily basis during the 75th campaign, and produced 300,000,000 pounds, or 3 million hundredweight, of sugar during that year. For the 75th campaign, Don Gorsek headed the factory team as District Manager. Russ Fullmer held the position as Agriculture Manager, Lynn Powers acted as Production Manager, Dan Rootes lead the maintenance crew, and Eldon Moos worked as Personnel Manager. Kevin Roth headed the Accounting Department, Richard Metcalf had charge of the warehouse operations, and Dave Cummings held the position of Technical Services Supervisor, overseeing both tare lab and factory lab operations. |