|

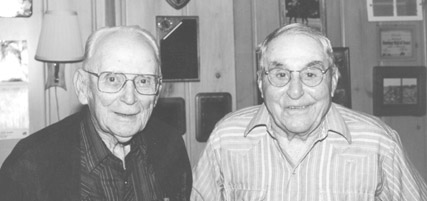

No other generation has seen so many changes in a lifetime as has the generation of James L “Bud” Starr and Carlos Collins, two octogenarians from the Fairview area. That generation has gone from horse and buggy to cars to planes to seeing men walk on the moon, they have seen great strides in technology, and they have also witnessed changes that have altered the face of farming forever. “You needed to be a hard worker, a good horseman, and be tough,” recalls Starr, speaking of farming during the years prior to the advent of power driven equipment. “It wasn’t enough to just be a good worker. If you weren’t tough, you wouldn’t make it.” These two gentlemen, both from the Fairview area, grew up as neighbors whose families worked the land and grew sugarbeets, using teams of horses for planting, cultivating, ditching, harvest, and hauling. When Holly Sugar opened its doors in 1925, sugarbeet production in the valley skyrocketed. “Fifty acres of beets was a lot of beets in those days,” Collins reminisces. “An average field was generally from 30 to 40 acres.” In good conditions, a farmer could use a two-horse team to farm, using these heavy Percheron or Belgian horses to plow, plant, ditch and for harvest. Muddy conditions required more horsepower. The whole farming process took a lot of time, “but we didn’t know it was slow,” laughs Starr. “We thought we’d done a heck of a job if we got a few acres a day done.” Working the fields began at sunup and lasted until

dark. Farmers always stopped for a large meal at noon, feeding and resting

the horses at the same time. Everyone had huge appetites, and “no one ever

complained about the food,” states Starr. Farmers used four row planters, pulled by two horses, to get the seeding done. “It was tough to keep the rows straight,” Starr says. Horses also pulled the ditching equipment for irrigation. “That was tough,” Collins says. He adds, “Of course, irrigation never did get easy. Even today, it’s a lot of work.” Both men agree harvest was long, hard and slow. “Today, machines top beets, lift them, load them on trucks, haul them to the beet dumps, and they are done.” Collins says. “Back then, we did it all by hand.” Farmers began harvesting beets around the first of October. Holly had beet dumps up and down the valley, but the company closed the dumps on Sundays. “My dad always said that even if a man had no religion, he still needed to rest his horses on Sunday,” Collins states. Horses worked hard six days a week and needed a day off to rest. “If anyone worked on a Sunday, the whole community talked,” Collins adds. It took a month to six weeks to harvest a 40-acre beet crop. “I can remember working at the harvest with Thanksgiving only a few days away,” Collins says. “We didn’t always get the beets out in time, either. One year we had 40 acres and we lost 20 of those acres to freezeup.” Harvest progressed slowly, even under ideal conditions. After horse drawn equipment lifted the beets, teams of horses drew a narrow V implement over the soil, smoothing and leveling the ground wide enough to pile the topped beets. Hand labor pulled the beets out of the ground, smacking them together to loosen and remove dirt. They then used hand knives to top the beets. Finally, the men threw the topped beets in piles for the haulers. Teams pulling wagons came down the rows, and the wagon drivers loaded beets into the wagons using beet forks. These forks, about four inches wider than a scoop shovel, were tined, which allowed the dirt to fall back to the ground rather than ending up in the wagon. Wagons held from 1˝ to 2 tons of beets. “Two tons was a good load for horses,” Starr points out. Once a driver got his wagon loaded, he and his team hauled the sugarbeets to the nearest dumpsite. Wagon boxes were designed to tip, allowing for easier unloading at the beet dumps. Drivers would bring the tare back with them, dump it in the field, then begin the loading process all over again. If a farmer had a lot of beets, he might use five or six teams during harvest. “It depended on how good the shovelers were as to how long it took to load a wagon,” Starr says. “If a farmer wasn’t too far from a dump, a good worker could make two trips in the morning and two trips in the afternoon.” If fall rains came during harvest, farmers hitched two or three teams to a wagon to get it out of the field. Collins laughs, “With a 2˝-ton load, wagons would sink to the axles. We needed extra teams to get those wagons out of the field.” “Harvest was really tough,” Starr acknowledges. “It could be cold, wet and muddy. But we never thought about it as tough. That’s the way it was, so you did it and didn’t give it another thought.” He admits, “I wouldn’t want to do it again, however.” Collins recalls one wet, very difficult fall. It appeared as if the farmers would not get the crop out in time. “The whole business community at Fairview pitched in to help,” says Collins. “They closed the stores at noon every day for two weeks, and everyone went to the field to help top beets. That’s what you call a community effort.” The advent of power driven equipment changed the face of farming forever. It took less than two years for farmers to switch from nearly all horses and few tractors to nearly all tractors and few horses. Collins, along with his father and a brother-in -aw, Kenneth Gardner, started an implement dealership in 1935, and in 1935 and 1936 the business accepted over 500 head of horses on trade for cultivator tractors. “Those two years saw the horse days come to an end,” Collins points out. “New equipment really changed farming. Farmers could increase acres, and do things faster and better. It was a whole new deal.” He adds, “Where we farmed 40 acres of sugarbeets, today they farm 400 acres or more.” Starr agrees. “Forty acres was a lot of beets to us. There are no limits to what they do today.”

|

Sugarbeets:

Sugarbeets: