Resources - Pests |

Nematode Control

|

Table of ContentsMore Information:

|

1. Introduction

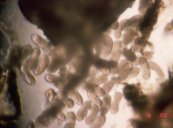

Click image for full page view.

The beet cyst nematode (Heterodera schachtii) is the most consequential type of nematode to sugar beet crops. Its effects on the sugar beet have been studied for over a hundred years. The nematode was first identified as a disease source in 1859 by in Germany by H. Schacht. Beet cyst nematodes occur in most parts of the world where sugar beet crops are grown. They occur in 17 states in the United States, and in over 40 countries around the wide. H. schachtii has a wide host range, including at least 218 plant species and 23 families. Host crops include commercial crop plants, ornamentals and weeds. Crop plant hosts include sugar beet, table beet, spinach, radish, turnip, broccoli, cabbage, cauliflower, rhubarb and tomato.

2. SymptomsOne of the first symptoms of H. schachtii infection is the appearance of patches of stunted plants which wilt before other plants in less infested areas. H. schachtii can either effect only localized areas or entire fields. When local infestations occur, well-defined circular areas of reduced and poor plant growth are observed. The infected plants have small tap roots with many lateral roots. The nematode cysts can be observed on the lateral roots as small, white cysts about 6 weeks after infection. In heavily infected soil, seedlings may either be killed before emergence, have delayed emergence, or die soon after emergence. This is called damping-off. Infected seedlings have unusually long petioles. Infected plants often display permanently stunted growth. Leaves of severely effected plants may turn a yellow color.

3. Life CycleAfter fertilization, an adult female can produce up to 600 eggs. The eggs hatch into larvae, which undergo four molts called J1-J4 (J stands for Juvenal) before attaining adulthood. The larvae look much like the adults in structure and appearance. The J1 molt occurs while still in the egg. The J2-stage larvae may hatch if soil moisture is sufficient. If the soil is dry, they can remain dormant until root exhudate from host plants stimulates hatching. The J2-stage larvae hatch into the soil and move to invade host plant roots. After penetrating the host root, the J2 larvae migrate to the cortical tissue and become sedentary parasites feeding off of the plant's resources. The larvae undergo the last 3 molts, and reach adulthood. Adult females remain attached to the root. Their bodies swell and break through the root surface, forming the white, lemon-shaped cysts that can be seen attached to fibrous roots. Adult males emerge into the soil and fertilize the sedentary females. By 30 days after the initial penetration by the J2-larvae, the female's body cavity is filled with up to 600 eggs. The female dies, and her body hardens into a reddish-brown cyst. Within the cyst, the eggs undergo the first molt and emerge as J2 larvae and the cycle begins again.

4. ControlOne of the most effective forms of control is crop rotation with non-host crops. The length of time a non-host crop should be planted varies with location. In the California Imperial Valley, 3 years is the minimum length of time, while in the California Salinas Valley 2 years can be sufficient time for reduction of nematode populations levels. In general, sugar beet crops should not be planted until 3-7 years after the infestation. The length of time depends in the severity of the infestation and how local conditions effect the nematode population. Planting sugarbeets early allow the beet to establish root systems which withstand later attacks by nematodes when the soil warms up. Fumigants can effectively control nematodes, however, effectiveness of fumigants is dictated by factors such as soil pH, soil temperature/moisture, depth of application, soil type, compaction, and organic matter content. The use of trap crops such as radish and mustard do effectively reduce nematode populations. Another method of control is early planting, while soil temperatures are low. The lower temperature decreases the rate of hatching and invasion. This gives the plant enough time to grow a large enough root system to help withstand later nematode attack. Chemical treatments include fumigants containing halogenated aliphatic hydrocarbons, and treatments of aldicarb at planting time. Also used are granular nematicides or nematide-resistant catch crops. Research is underway to develop sugarbeet varieties that are resistant to sugarbeet nematodes, but acceptable varieties with nematode resistance are not yet available.

|

There are at least 29 species of nematodes that are parasitic on

sugarbeets. Nematologists and plant pathologists agree that nematodes are a major

pest afflicting sugarbeet production. Field infestations may affect one or more

localized areas or entire fields. Localized infestations produce well defined

circular areas where plant growth is reduced or stands are poor. Other hosts for

sugarbeet nematode include spinach, radish, turnip, cabbage, and tomato. Common weed

hosts include mustard, pigweed, lambsquarters, smartweed, curly dock, and nightshade.

There are at least 29 species of nematodes that are parasitic on

sugarbeets. Nematologists and plant pathologists agree that nematodes are a major

pest afflicting sugarbeet production. Field infestations may affect one or more

localized areas or entire fields. Localized infestations produce well defined

circular areas where plant growth is reduced or stands are poor. Other hosts for

sugarbeet nematode include spinach, radish, turnip, cabbage, and tomato. Common weed

hosts include mustard, pigweed, lambsquarters, smartweed, curly dock, and nightshade.