Resources - Pests |

Insect Control |

Table of ContentsMore Information: |

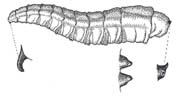

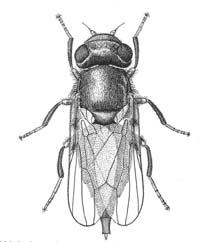

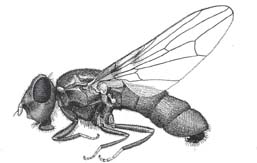

1. IntroductionSugar beet root maggots are probably the most destructive sugar beet insect pest in the United States. They primarily occur in the Rocky Mountain and Red River Valley growing areas. The root maggot is the larvae of a small two-winged fly. The maggot overwinters as a full grown larvae in previously planted sugarbeet fields. During the Spring they pupate close to the soil surface. In mid May, the flies emerge and migrate to nearby beet fields. In loose ground, the female enters cracks near the beet and deposits up to 200 eggs in small clusters. If the soil is compact, the eggs are deposited just below the surface, often in contact with the plant, but never more than an inch away from it. The eggs hatch in a few days and the larvae begin feeding on the roots. They continue doing so until they become full grown in August. They then leave the beet plants, but remain in the soil immediately below and around the beet plants. Usually one generation is produced per year, although adult flies have been found in late summer. Eggs from root maggots are also deposited around lambsquarters, redroot pigweed, and prostrate pigweed.

2. DamageSugar beet root maggot larvae scrap the surface of the beet with their mouth hooks. Root maggots can completely severe a small beet which then wilts and dies. If maggots are very numerous, a stand of beets may become so reduced that replanting is necessary. Injury always takes place at a point below the upper limit of soil moisture. The feeding of the maggots causes the sap of the beet to escape, causing the soil to become moist around the injury. This moistened soil eventually hardens and forms a clod around the injured root. Damage is usually most severe on light soil areas. If sugar beets are planted in an infested field, the larvae may attack the germinating seed; feeding on the succulent underground portions of the newly emerged seedling.

3. Identification

4. Root Maggot ControlThree factors should be considered before spraying:

Root maggot damage can be reduced by controlling soil moisture. The maggots are only found in moist soil. Therefore, as the soil dries out, the maggots are forced deeper into the soil. If this happens when the beets are young, the deep feeding on the beet roots will result in a greater loss as a result of the roots being severed. Irrigating will hold the maggots closer to the surface where the feeding is not as injurious. The beets are able to develop faster under irrigated conditions and this too will increase resistance to maggot injury. If the soil dries rapidly, the maggots get caught in dry soil where they lay dormant, without food, for long periods of time. Studies have shown they can be found alive and healthy even after two months in dry soil. Crop rotation provides limited control because the flies can travel considerable distances. Beets should no be planted in an infected field the following year. Plant as early as possible and irrigate frequently, so that the beets have developed to a point where they can resist root maggot attack. More information can be obtained from your crop consultant or by reading the additional root maggot control information.

|